Armenian brandy: from Soviet era to modern Ararat revival

Γιαννης Κοροβεσης•Articles

Original text in Greek

You don’t often get the chance to walk through the gates of a distillery whose products once played a role —as a diplomatic gesture or, perhaps, a liquid lubricant— in the negotiations between Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin. And yet, that’s exactly where I found myself, whilst at the Yerevan Cocktail Week: at the Yerevan Brandy Company, home of the legendary Ararat armenian brandy. And while I’ve visited distilleries in nearly every corner of the world, I can honestly say this one left an indelible mark, for reasons I’ll get into shortly.

Unlike Cognac, which is born of strict codes and the polished elegance of Bordeaux’s vineyard aristocracy, Armenian brandy is a spirit forged through hardship and heritage. Grown in high-altitude, volcanic terroir, shaped by a continental climate and centuries of adaptation, Armenian brandy doesn’t follow a rigid playbook, yet it has soul. Deep, spicy, complex soul. And although its post-Soviet market identity was for years muddled (for decades it was sold under the label “Konyak”), it has now emerged with clarity, character, and confidence.

Από το σεμινάριό μου στο Γερεβάν με τίτλο: Armenian brandy vs Cognac – The Grand Slam in Yerevan

Armenians have been making wine since roughly 4000 BCE, but distillation only entered the scene in the 19th century. Initially, it was mostly fruit-based spirits —cherry and berry eau-de-vie— but the shift to wine-based brandy came thanks to a man named Nerses Tairyan, an Armenian merchant who studied viticulture and distillation in France. In 1887, together with his cousin Vasily Tairyan, he planted new vineyards and founded what would later become the Yerevan Brandy Company.

The company began brandy production in 1894, at an industrial scale, and in 1899 was leased (and later purchased) by Nikolay Shustov, a Russian liquor distributor who expanded its reach across Eastern Europe. Legend has it that Shustov secretly submitted his Armenian brandy to a blind tasting at the 1900 Paris World’s Fair, where it was mistaken for fine Cognac and awarded the Grand Prix. Upon revealing its origin, he was allegedly granted permission to use the term “Cognac” on his labels — a practice that, in those pre-EU, pre-regulation days, was not unheard of. After all, even Greek Metaxa was once labeled “Cognac”. But that’s another story.

From Soviet symbol to global revival

In 1920, with the establishment of Soviet Armenia, the company was nationalized. The Yerevan Brandy and Wine Trust was given a monopoly over Armenian brandy production, just as Georgia was designated the official wine supplier of the USSR. It was during this era (mid-20th century) that the brandy became known as Ararat, earning a revered place among Soviet leaders, diplomats, and European visitors alike.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the factory lost its monopoly. In 1998, in a twist only history could script, the Yerevan Brandy Company was privatized and sold to Pernod Ricard for $30 million, through a competitive bidding process involving Merrill Lynch and New Zealand’s Admiralty Investment Group. From the ashes of a fallen system, Armenian brandy was reborn, nowwith global reach and renewed prestige.

Η επίσκεψή μου στο Yerevan Brandy Company

Terroir, grape and grit

Armenian brandy grapes grow not on rolling hills as in Cognac, but on high-altitude, volcanic terrain (800 to 1,200 meters above sea level) in regions like Ararat Valley, Tavush, Vayots Dzor, and Artsakh (also known as Nagorno-Karabakh), a region with a long and complex history of territorial disputes and political tension between Armenia and Azerbaijan. The climate is extreme: hot, dry summers and freezing winters. The result? Grapes with rich sugar and acid balance, ideal for expressive distillates. Local varieties like Voskehat, Kangun, Garan Dmak, and Banants lend distinct character —bold, floral, spicy, and unmistakably Armenian.

Fermentation & distillation

As in Cognac, a dry white base wine is fermented —typically to 10–12% ABV. The aim is freshness, acidity, and minimal spoilage risk before distillation. Distillation follows the Charentais double-distillation method, using copper pot stills. Importantly, continuous stills are banned for true Armenian brandy. In top-tier houses like Ararat, quality trumps volume.

Maturation in Caucasian oak

Armenian brandy matures in Caucasian oak barrels, sourced from forests in Artsakh and Tavush. These oaks have tighter grain than French oak, contributing notes of walnut, vanilla, cocoa, clove, and a resinous, earthy sweetness that defines the Ararat style.

Thanks to the climate and the grape DNA, maturation is accelerated. The angel’s share can reach 3–4% per year, and even a 3-year-old spirit shows impressive depth and integration.

From Yalta, with love

One of Armenian brandy’s most iconic stories involves the 1945 Yalta Conference, where Stalin offered Churchill a glass of Ararat Dvin. The British Prime Minister was reportedly so impressed, he requested 400 bottles per year — a tradition said to have continued until his death. While historians debate the specifics, Armenians fondly repeat one of Churchill’s most quoted (and possibly apocryphal) lines:

“Cuban cigars, Armenian brandy, and no sport — the secrets to a long life.”

Categorization and Market

Today, Armenian brandy is categorized by aging:

-

Ordinary (3–5 years)

-

Branded (minimum 6 years)

-

Collection (blends aged at least 3 additional years after blending)

Roughly 90% of Armenian brandy is exported, historically to former USSR countries. In Russia, it continued to be labeled “Konyak,” while in Europe it appeared as “Armenian brandy.” Following Pernod Ricard’s acquisition and long negotiations with the EU, the company officially dropped the “Konyak” name — especially after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which led Pernod Ricard to withdraw from the Russian market.

Today, Ararat is distributed globally — proudly labeled as Armenian Brandy.

Visiting the temple of Armenian brandy

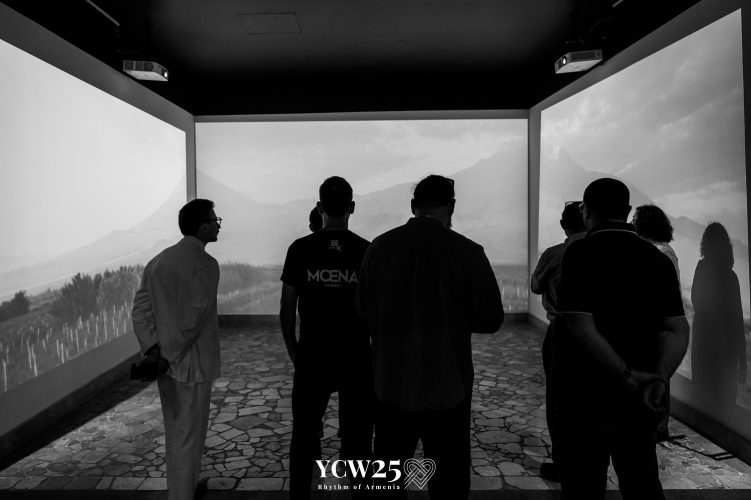

During my visit to Yerevan Cocktail Week, just before delivering a talk comparing Cognac and Armenian brandy, I had the privilege of touring the Yerevan Brandy Company. Towering above the city, with Victory Bridge behind me and endless rows of oak casks ahead, it felt more like a temple than a factory.

Inside, I walked past commemorative barrels bearing the names of global leaders — including two former Greek presidents. I saw rare bottlings, dusty old labels, and displays chronicling a journey through war, revolution, rebirth, and modern luxury. It was a time capsule and a powerful reminder that some spirits carry far more than aroma and ABV. They carry history.

Tasting Ararat

During my stay, I tasted countless expressions — from the entry-level Three Stars to the majestic Nairi 20 Year and the legendary Dvin Reserve. Ararat brandies exhibit a distinctive profile: dried apricot, fig, plum, toasted walnut, sweet spice, cocoa, and just a hint of coffee bitterness. Even the younger expressions are smooth, mellow, and well-integrated, no harsh alcohol burn, no cloying vanilla. Just rich, warming texture, long finish, and unmistakable character.